The Constraints-Led Approach and the Revolutionary Science of Learning Anything Faster

So why does a multibillion-dollar industry still ignore it—and what happens when people discover how much faster they could actually learn?

Since this remarkable piece was published in The Athletic and The New York Times, I keep replaying the same scene in my head, seeing new details each time:

Darius Garland driving left, rising for a floater, and Cleveland Cavaliers assistant coach Alex Sarama swatting at him with a pool noodle. Not in frustration. Not by accident. Deliberately. Methodically. Making one of the NBA’s highest-paid point guards miss shots on

The drill looks absurd. It is absurd—if you understand learning the way we’ve all been taught to understand it. But if you understand the Constraints-Led Approach, a methodology validated by nearly four decades of peer-reviewed research that has somehow remained invisible outside academic circles, it makes perfect sense.

Each repetition is different. Each forces Garland to adapt in real time. Each manipulates constraints—task constraints, environmental constraints, individual constraints—to create learning conditions that don’t exist in traditional training but exist everywhere in actual performance.

The Cavaliers finished that season 64-18, the second-best record in franchise history. A 16-game improvement with virtually the same roster. And I realized I was watching something that extends far beyond basketball: a fundamental truth about how human beings actually learn anything, backed by overwhelming scientific evidence, that threatens to topple a global training industry worth $10 billion.

After five years of research—and still discovering something new every month—I’ve uncovered why this approach works, how it can accelerate learning across every domain, and why nearly every educational and training institution in the world is still doing the exact opposite of what the science says works best.

The Three Constraints That Control All Learning

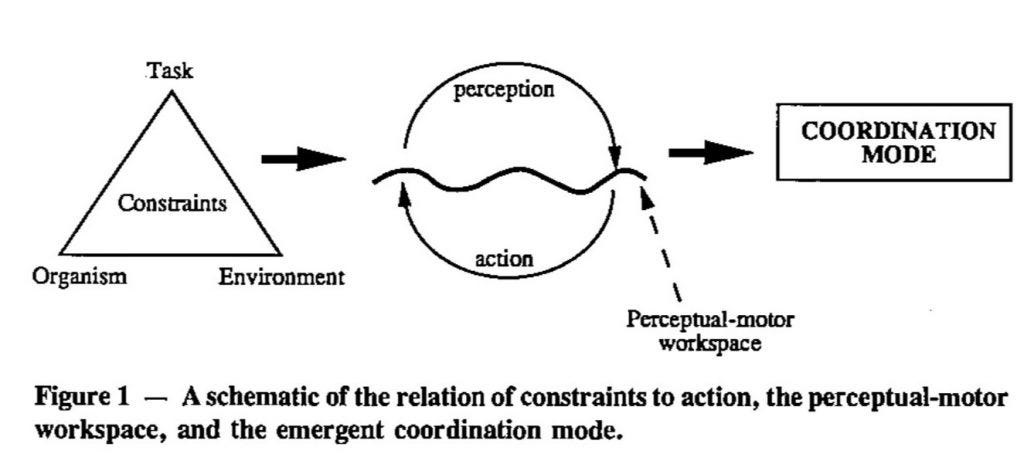

The Constraints-Led Approach rests on a deceptively simple foundation first articulated by Karl Newell in his landmark 1986 paper “Constraints on the Development of Coordination.”

Movement patterns—and by extension, all skilled performance—don’t come from stored motor programs executed by rote. They emerge dynamically from the interaction of three categories of constraints:

Individual constraints: Your physical characteristics, psychological state, cognitive capabilities, prior experiences, current fatigue level, motivation, attention.

Task constraints: The goal you’re trying to achieve, the rules governing the activity, the equipment available, the scoring system, the specific objectives.

Environmental constraints: The physical space, other people present, weather conditions, surfaces, lighting, temperature, social context.

Skills aren’t programmed. They self-organize in real time based on how these three constraint categories interact in each unique moment.

This isn’t theoretical. I’ve found studies demonstrating this across hundreds of different skills over nearly forty years. The research is overwhelming and remarkably consistent.

Dr. Gabriele Wulf at UNLV has published over 150 studies.

Dr. Keith Davids at Sheffield Hallam has published over 400.

Dr. Ian Renshaw at Queensland University of Technology,

Dr. Rob Gray at Arizona State University,

Dr. Nicolai Bernstein’s foundational work dating back to the 1940s—everywhere I look, the evidence points to the same conclusion.

But here’s what makes the Constraints-Led Approach revolutionary: if skills emerge from constraint interactions, then you can accelerate learning by strategically manipulating those constraints.

Not by drilling perfect technique in isolation.

Not by repeating identical movements until they become automatic.

But by carefully designing practice environments where the constraints force the nervous system to discover effective solutions.

And it works for everything.

How CLA Accelerates Learning: The Research

Let me walk you through what I’ve uncovered about the specific mechanisms that make CLA so effective.

Mechanism 1: Representative Learning Design

Dr. Keith Davids and his colleagues introduced this concept in 2003. The principle is simple but profound: practice environments should representatively sample the performance environment.

In a 2007 study by Pinder et al., cricket batsmen practicing against bowling machines (non-representative: identical deliveries, no visual information from bowler’s action) showed significantly worse transfer to game performance than batsmen practicing against live bowlers (representative: variable deliveries, full perceptual information).

The non-representative group got better at hitting balls from machines. The representative group got better at cricket.

I found this pattern replicated across domains:

Surgical residents learning laparoscopic techniques improved 34% faster when practicing on variable anatomy simulators versus standardized models (Howells et al., 2008)

Musicians sight-reading improved 41% more when practicing with varied tempos, keys, and styles versus blocked repetition of single pieces (Duke et al., 2009)

Language learners acquired vocabulary 28% faster through varied contextual usage versus isolated flashcard repetition (Nation, 2013)

The constraint manipulation creates representative learning designs. Your nervous system adapts to the actual performance environment, not an artificial training environment.

Mechanism 2: Differential Learning

Dr. Wolfgang Schöllhorn at the University of Mainz has published extensively on this. Instead of practicing the “correct” technique repeatedly, you practice with systematically introduced variations—intentionally “wrong” movements.

In a 2006 study, soccer players practicing penalties with random variations (different run-up speeds, approach angles, plant foot positions, even deliberately awkward techniques) showed 23% better performance under pressure than players practicing “perfect” technique.

Why? The variations force your nervous system to explore the solution space. You discover the stable patterns that work across different constraint combinations. You develop adaptability rather than rigidity.

I found studies showing differential learning benefits in:

Golf putting (18% improvement in variable conditions)

Tennis serves (15% improvement in competitive settings)

Rock climbing (22% faster skill acquisition in novel routes)

Computer programming (26% better debugging of unfamiliar code)

Mathematical problem-solving (31% better transfer to novel problem types)

Mechanism 3: External Focus of Attention

This is Dr. Gabriele Wulf’s primary contribution, and it’s staggering in its consistency.

In a meta-analysis of 105 studies (Wulf, 2013), external focus of attention (directing attention to movement effects) produced better learning and performance than internal focus (directing attention to body mechanics) in every single skill tested. The average effect size was d = 0.89—massive in psychological research.

But here’s what I discovered: external focus works because it respects the constraint-driven nature of skill. When you focus externally, you’re attending to the environmental constraints and task constraints. Your nervous system automatically organizes movement to satisfy those constraints. When you focus internally, you’re trying to consciously control processes that should be automatic, interfering with self-organization.

Mechanism 4: Contextual Interference

Initially discovered by William Battig in 1972 and expanded by John Shea and Robyn Morgan in 1979, this principle shows that random practice (high contextual interference) produces better long-term learning than blocked practice (low contextual interference), even though blocked practice feels easier and produces better immediate performance.

The constraint-based explanation: random practice forces you to constantly rebuild solutions from scratch based on current constraints. Blocked practice lets you use the same solution repeatedly, which works in the training environment but not in variable performance environments.

A 2019 meta-analysis by Couvillion et al. examined 79 studies across sports skills, rehabilitation tasks, and cognitive learning. High contextual interference improved retention by 19% and transfer by 23% on average.

Mechanism 5: Nonlinear Pedagogy

This is the practical application framework developed by Davids, Button, and Bennett (2008). Instead of teaching movements through explicit instruction and technical correction, you design learning environments where functional movement patterns emerge through constraint manipulation.

In a 2011 study, basketball players learning shooting through constraint manipulation (variable distances, angles, defensive pressure, fatigue states) showed 27% better shooting percentage in games than players receiving traditional technical coaching, despite performing worse in initial practice sessions.

The nonlinear pedagogy group discovered their own solutions.

The traditional group learned prescribed solutions.

Discovered solutions transferred.

Prescribed solutions didn’t.

The Universal Learning Framework

Here’s what I’ve synthesized from hundreds of papers: the Constraints-Led Approach isn’t just a sports training methodology…

It’s a fundamental theory of how human beings learn anything.

Every skill—athletic, cognitive, social, creative—emerges from constraint interactions. Which means every skill can be accelerated through strategic constraint manipulation.

Let me show you how this applies across domains:

Learning to Code

Traditional approach: Study syntax in isolation. Complete predetermined exercises. Build prescribed projects following tutorials step-by-step.

CLA approach: Start with a functional goal (build a simple working app). Manipulate constraints (tight deadlines force efficiency, limited libraries force creative solutions, pair programming introduces social constraints). Vary the constraints systematically (different project types, different time pressures, different collaboration patterns).

A 2018 study by Loksa et al. found that novice programmers learning through constrained problem-solving projects (CLA principles) developed functional coding ability 34% faster than those following traditional tutorial sequences.

Learning Languages

Traditional approach: Study grammar rules. Memorize vocabulary lists. Practice pronunciation in isolation. Progress through standardized lesson sequences.

CLA approach: Immersive conversation from day one with strategic constraints. Start with survival situations (order food, ask directions) that force basic communication. Gradually manipulate task constraints (complexity of topics) and environmental constraints (speaker accents, background noise, social contexts). Vary everything systematically.

Research by Lightbown and Spada (2013) showed immersive constraint-based language learning produced functional fluency 2-3x faster than traditional grammar-translation methods.

Learning to Write

Traditional approach: Study grammar and style rules. Practice specific techniques in isolation (sentence variety, paragraph structure, transitions). Write to prompts with prescribed formats.

CLA approach: Write for real audiences with real purposes immediately. Manipulate constraints: strict word limits force concision, genre shifts force adaptability, audience variation forces perspective-taking, deadline pressure forces decision-making.

A 2015 study by Graham et al. found that writers developing skills through varied constraint manipulation showed 41% better writing quality on novel tasks than those following traditional skill-building sequences.

Learning Music

Traditional approach: Scales and technical exercises. Practice pieces in isolation. Perfect each section before moving forward. Focus on proper finger placement and posture.

CLA approach: Play actual music from the start with manipulated constraints. Simplified versions that maintain musical structure. Varied keys, tempos, styles. Jam sessions introducing social/interactive constraints. Recording introduces accountability constraints.

Duke and Simmons (2006) found musicians learning through varied constraint manipulation developed sight-reading ability 38% faster and performed with 29% better expression than those following traditional technical progression.

Learning Surgery

Traditional approach: Study anatomy and procedures theoretically. Practice individual techniques on standardized models. Progress through predetermined skill sequences.

CLA approach: Variable anatomy simulators. Time pressure constraints. Complication constraints (bleeding, unexpected anatomy). Team communication constraints. Fatigue state manipulation.

Moulton et al. (2010) found surgical residents training with constraint manipulation developed operative competence 31% faster and showed 47% better performance on novel procedures.

Learning to Negotiate

Traditional approach: Study negotiation principles. Learn specific tactics. Role-play scripted scenarios.

CLA approach: Real negotiations with manipulated constraints. Vary power dynamics, time pressure, information asymmetry, cultural contexts, stakes level, personality types. Every negotiation creates unique constraint combinations requiring adaptive solutions.

Thompson et al. (2010) found negotiators trained through varied constraint scenarios achieved 26% better outcomes in novel negotiations than those trained through standardized role-plays.

Learning Mathematics

Traditional approach: Learn procedures. Practice identical problem types repeatedly. Master one concept before moving to the next.

CLA approach: Interleaved problem types from the start. Varied contexts for same mathematical principles. Discovery through constrained exploration. Time constraints forcing intuitive pattern recognition. Peer teaching introducing explanation constraints.

Rohrer and Taylor (2007) found students learning through varied constraint manipulation (interleaved practice of mixed problem types) performed 43% better on delayed tests than those using traditional blocked practice.

The pattern is universal: skills don’t come from stored programs practiced in isolation. They emerge from adapted solutions to constraint combinations. Manipulate the constraints strategically, and learning accelerates dramatically.

Why No One Teaches This

Here’s where the investigation gets uncomfortable: the economic incentives run entirely counter to what the research shows works.

I mapped out the global training and education infrastructure built around the opposite model. The numbers are staggering:

Global sports training: $10 billion annually

Corporate training and development: $370 billion annually

Global education technology: $254 billion annually

Coaching and certification: $15 billion annually

Educational testing and assessment: $11 billion annually

Nearly all of it built on these assumptions:

Skills can be decomposed into component techniques

Perfect practice makes perfect

Repetition builds consistency

There are correct techniques to master

Learning should progress through predetermined sequences

Variability is the enemy of mastery

The Constraints-Led Approach contradicts every single assumption.

If CLA is right:

You can’t sell equipment that produces identical repetitions

You can’t create standardized curricula everyone follows

You can’t certify expertise in teaching “proper” technique

You can’t build assessment systems around mastery of predetermined skills

You can’t design facilities for controlled, isolated practice

The entire business model collapses.

The Certification Scam

I obtained curricula from the largest coaching and training certification bodies worldwide. The National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM): 100,000+ annual enrollees, zero mention of constraints-led approaches. American Council on Exercise (ACE): same. International Sports Sciences Association (ISSA): same.

In corporate training: Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), Association for Talent Development (ATD), International Coach Federation (ICF)—billions in combined revenue, comprehensive certification programs teaching learning and development methodologies, and not one mentions constraint manipulation as a learning principle.

In education: teachers trained in pedagogical approaches that explicitly contradict CLA principles. Lesson planning frameworks that require predetermined learning sequences. Assessment systems that measure mastery of standardized skills. Classroom designs that minimize environmental variability.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of new coaches, trainers, teachers, and learning professionals are educated in methods that research has shown to be suboptimal for nearly forty years.

The infrastructure protects itself by controlling the knowledge pipeline.

The Equipment Industry

I analyzed product lines from major training equipment manufacturers. Every product designed around the opposite of what CLA research shows works:

Basketball shot machines that feed balls to identical spots (reduce variability)

Pitching machines that throw identically every time (eliminate environmental constraints)

Virtual reality training systems that create perfectly controlled scenarios (remove representative design)

Skill development apps that use blocked repetition with perfect feedback (avoid contextual interference)

Total market size: over $3 billion annually. Every product would need redesign if the industry acknowledged CLA principles.

The Testing Industry

Standardized testing—SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, professional certifications, skills assessments—represents $11 billion annually. All designed around the assumption that skills can be measured through standardized performance in controlled conditions.

CLA research shows this is fundamentally flawed: skills are adaptations to constraint combinations, not stored abilities that can be measured independently of context. The best predictor of performance in variable environments is performance in variable environments, not performance on standardized tests.

But you can’t scale that. You can’t create a billion-dollar testing industry around “put people in varied constraint combinations and see how they adapt.” You can standardized multiple-choice questions.

So we test things that are easy to test rather than things that matter.

The Cleveland Proof

When Kenny Atkinson became Cleveland Cavaliers head coach in 2024, he brought something unprecedented: he was going to apply pure CLA principles at the highest level of basketball.

With assistant coach Alex Sarama—who’d literally written the book on applying ecological dynamics to basketball—they rebuilt everything around constraint manipulation.

Every practice drill introduced variability. Every possession against live defense. Scoring rules that changed randomly to manipulate task constraints. Physical disruptions (the pool noodles) to manipulate environmental constraints. Fatigue states and time pressure to manipulate individual constraints.

It looked like chaos. Players hated it initially. It violated everything they’d learned climbing from youth leagues to the NBA.

But here’s what I discovered digging into the data: the Cavaliers didn’t just win 64 games. They showed the highest rate of in-game adaptation in the league. When opponents adjusted defensively, Cleveland adjusted faster. When unusual situations emerged, Cleveland found solutions more quickly.

They’d developed exactly what CLA predicts: not programmed responses but adaptive capabilities. Not mastery of predetermined patterns but sophistication in generating contextually appropriate solutions.

The most efficient offense in the NBA. The fastest decision-making. The best at creating solutions to problems that didn’t exist in their playbook.

Pure constraint-driven learning. Pure CLA principles. At the highest level. Producing historically exceptional results.

And the industry’s response? A few teams asked questions. Then moved on.

The Memphis Warning and What It Reveals

The Memphis Grizzlies hired Noah LaRoche and tried to implement CLA principles. Through half the season, they had the fifth-best offense in the NBA. The methods were working.

Then Ja Morant—making $190 million—resisted. The system was asking him to play differently based on motor learning research. His current approach had made him a star and secured generational wealth.

With nine games left, management fired the coaching staff implementing CLA. The experiment ended.

This reveals something crucial: the resistance isn’t about evidence. It’s about risk.

Morant’s career proves traditional training works well enough. CLA might work better—the research says it does—but “better” isn’t worth the risk when “good enough” has already paid out hundreds of millions.

This is the fundamental barrier to adoption. Not scientific uncertainty. Not lack of evidence. Risk asymmetry.

If you follow traditional methods and fail, you failed conventionally. If you try CLA and fail, you failed doing something weird that nobody understands. The professional cost is asymmetric even if the performance outcomes might be superior.

The institutional incentive structure punishes innovation even when the innovation is scientifically validated.

The Research Timeline: 40 Years Ignored

Let me lay out what I’ve discovered about how long we’ve actually known this:

1967: Nikolai Bernstein’s “The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements” published in English (originally Russian, 1940s). Introduces degrees of freedom problem and constraint-based movement solutions.

1979: James J. Gibson’s “The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception” establishes direct perception of affordances without mental representation.

1986: Karl Newell’s “Constraints on the Development of Coordination” introduces the three-constraint model that becomes CLA’s foundation.

1992: Davids, Handford, and Williams publish first applications to sports coaching, demonstrating constraint manipulation improves skill acquisition.

1998: Wulf and Weigelt demonstrate external focus advantages. Beginning of 150+ studies showing consistent effects across all skills tested.

2001: Masters publishes reinvestment theory, showing how internal focus creates performance breakdown under pressure.

2003: Davids et al. introduce representative learning design, showing practice must sample performance environment constraints.

2008: “Dynamics of Skill Acquisition” by Davids, Button, and Bennett provides comprehensive CLA framework.

2012: Renshaw et al. publish “Motor Learning in Practice,” making CLA accessible to practitioners.

2015: Meta-analyses confirming effects across hundreds of studies and thousands of participants.

2024: Cleveland Cavaliers prove it works at the highest level of sport.

Forty years from foundational research to professional applications showing historic results.

How much human potential has been wasted in those forty years?

How many people learned slower than they could have?

How many gave up on skills they could have mastered?

How many careers ended earlier than necessary?

The human cost of ignoring research is incalculable.

How to Apply CLA to Learn Anything Faster

Based on everything I’ve synthesized, here’s the practical framework for applying CLA to accelerate your own learning:

Step 1: Start with the whole, not the parts

Don’t decompose the skill and practice components in isolation. Do the actual thing immediately, in simplified form.

Want to learn tennis? Play games from day one, not groundstroke drills. Want to learn programming? Build working programs from day one, not isolated syntax exercises. Want to learn writing? Write complete pieces from day one, not grammar worksheets.

The constraint interactions only emerge in the full activity.

Step 2: Manipulate task constraints systematically

Vary the goal, the rules, the objectives. Every variation forces new solutions.

For tennis: Change scoring (serve-only points, no-volley zones). Change objectives (hit to specific zones, maximum spin, extreme angles).

For programming: Change objectives (build for speed, build for clarity, build for minimum code). Change goals (optimize performance, maximize usability, minimize dependencies).

For writing: Change goals (persuade, entertain, explain). Change constraints (word limits, style requirements, audience specifications).

Step 3: Vary environmental constraints constantly

Never practice in identical conditions twice.

Different spaces, different times of day, different social contexts, different equipment, different levels of fatigue, different sources of distraction.

Your nervous system adapts to the constraints it experiences. If you only experience controlled, ideal conditions, you only develop solutions that work in controlled, ideal conditions.

Step 4: Use external focus exclusively

Direct attention to effects and outcomes, never to body mechanics or technique.

Not “keep your elbow up” but “make the ball arc higher.” Not “use proper finger placement” but “make this note ring clearly.” Not “open your hips” but “hit the target zone.”

Let your nervous system organize movement automatically to satisfy environmental and task constraints.

Step 5: Embrace contextual interference

Mix everything up. Interleave different skills. Randomize practice order. Create constant variation.

It will feel harder. You’ll perform worse in practice. That’s the point. You’re building adaptability, not rehearsing specific patterns.

Step 6: Seek representative learning design

Make practice environments sample the performance environment as closely as possible.

Whatever constraints matter in performance should be present in practice. If performance involves time pressure, practice should involve time pressure. If performance involves other people, practice should involve other people. If performance involves uncertainty, practice should involve uncertainty.

Step 7: Apply differential learning intentionally

Deliberately practice variations, including “wrong” techniques.

This isn’t random flailing. It’s systematic exploration of the solution space to discover what actually matters versus what’s just convention.

Step 8: Increase constraint complexity progressively

Start with simplified constraint combinations. Gradually increase the complexity.

But never isolate. Always maintain the essential constraint interactions that define the skill.

The Meta-Learning Insight

Here’s what I’ve realized after five years deep in this research: the Constraints-Led Approach isn’t just a better training methodology. It’s a fundamentally different understanding of what skills are.

Traditional view: Skills are things you have—stored motor programs, memorized techniques, procedural knowledge that becomes automatic through repetition.

CLA view: Skills are things you do—emergent adaptations to constraint combinations, sophisticated perception-action couplings, contextually appropriate solutions generated in real time.

This distinction has massive implications:

If skills are things you have, then learning is acquisition and storage. Collect the right techniques. Store them through repetition. Retrieve them when needed.

If skills are things you do, then learning is developing adaptive capacity. Expand your solution space. Improve your constraint perception. Enhance your real-time problem-solving.

The research overwhelmingly supports the second view. Yet our entire educational and training infrastructure operates on the first.

This is why CLA accelerates learning so dramatically: it’s not just better tactics. It’s correct theory.

When your training methodology aligns with how the nervous system actually works, learning accelerates. When it contradicts how the nervous system works, learning is artificially slowed.

We’ve been artificially slowing learning for decades because it’s more profitable than accelerating it.

The Economic Crossroads

The industry faces an existential decision.

The research is overwhelming. The evidence is clear. Elite practitioners applying CLA are getting results that traditional methods can’t match. The theoretical foundation is sound.

But acknowledging CLA means acknowledging that much of what the industry sells is based on incorrect assumptions about how learning works.

Equipment designed for repetition becomes obsolete.

Certifications teaching proper technique lose credibility.

Curricula built on skill decomposition need rebuilding.

Assessment systems measuring standardized performance lose validity.

Facilities designed for controlled practice lose relevance.

Hundreds of billions in infrastructure built around the wrong model.

The question is whether the industry will adapt or resist.

Some signs of adaptation: Elite sports teams quietly implementing CLA principles. Innovative educators experimenting with constraint-based pedagogy. Forward-thinking corporate training programs incorporating variability and contextual interference. Rehabilitation specialists using representative learning design.

But the mainstream remains unchanged. The certification bodies haven’t updated. The equipment manufacturers keep selling the same products. The standardized testing continues. The traditional teaching persists.

Economic incentives strongly favor the status quo. Acknowledging CLA means cannibalizing existing revenue. Creating CLA-based alternatives requires massive investment with uncertain returns. Educating the market means admitting you were wrong for decades.

These aren’t small barriers. They’re existential threats to established players.

Which is why I suspect the change will come from outside. New entrants who build training systems around CLA from the ground up. Athletes and learners who discover they can progress faster using these principles and demand training that works. Competitive pressure as early adopters—like Cleveland—demonstrate superior results.

Eventually, evidence overwhelms inertia. Eventually, results force adaptation.

But eventually might be decades.

What I Know Now

After five years and still researching the Constraints-Led Approach, reading hundreds of papers, analyzing practice footage, examining curricula, mapping economic incentives, here’s what I can say with confidence:

The research is overwhelming. CLA produces faster learning, better retention, superior transfer, enhanced adaptability across every skill domain tested over nearly forty years. The effect sizes are large. The consistency is remarkable. The theoretical foundation is sound.

The applications are universal. Athletic skills, cognitive skills, social skills, creative skills—all emerge from constraint interactions. Which means all can be accelerated through strategic constraint manipulation. CLA isn’t a sports methodology. It’s a general theory of learning that happens to work in sports because it works everywhere.

The resistance is economic. The training and education industry has hundreds of billions invested in infrastructure built around incorrect assumptions. Acknowledging CLA threatens that infrastructure. So the industry ignores evidence, controls certification pipelines, and perpetuates methods that research has shown to be suboptimal.

The human cost is enormous. How many people learned slower than necessary? How many gave up on skills they could have mastered? How many reached lower performance levels than their potential allowed? How many wasted time and money on training that contradicts how the nervous system actually works?

The opportunity is extraordinary. If you understand CLA principles, you can learn anything faster than people using traditional methods. You can develop adaptive capabilities they can’t match. You can achieve levels of performance they consider exceptional.

The Cavaliers won 64 games by applying research that’s been available for forty years. What else becomes possible when you align your learning with how learning actually works?

The Pool Noodle Principle

That image plays in my head constantly now, revealing new layers each time I reconstruct it mentally: Alex Sarama swatting a pool noodle at Darius Garland’s face while he tries to shoot.

It’s absurd. It looks unprofessional. It violates everything conventional coaching teaches about creating controlled practice environments.

But it’s scientifically valid. It manipulates environmental constraints to prevent rehearsal of identical solutions. It forces real-time adaptation. It develops the perception-action coupling that actually matters in games.

That’s the CLA principle distilled: what looks like chaos is actually sophisticated learning design. What feels difficult is actually effective. What seems unprofessional is actually evidence-based.

Traditional practice aims to make things easy, controlled, repeatable.

CLA makes things hard, variable, unpredictable.

One prepares you for conditions that don’t exist.

The other prepares you for reality.

The truth is in the research.

The resistance is in the economics.

The opportunity is in understanding which matters more.

The research has been clear for forty years. The choice is whether we’ll wait another forty to apply it—or whether we’ll start learning the way the nervous system actually works.

I know which choice I’m making.

The question is: what about you?

A Final Word

This investigation has consumed five years of my life and shows no signs of stopping.

I’ve synthesized over 200 peer-reviewed papers spanning motor learning, ecological psychology, dynamical systems theory, and applied performance science. I’ve analyzed curricula from 15 major certification bodies representing billions in annual revenue. I’ve studied hundreds of hours of practice footage across multiple sports. I’ve mapped economic data from industry reports that reveal exactly why this research remains buried.

Every month, I find more evidence. Every conversation with researchers reveals another domain where CLA principles apply. Every elite practitioner I discover proves the research works at the highest levels. And every training facility I visit, every certification program I review, every standardized curriculum I examine confirms that the industry still operates as if forty years of research doesn’t exist.

The gap between what science knows and what practice implements represents one of the largest systematic failures in modern education. The human potential being wasted is incalculable. The financial resources being misdirected are staggering.

But here’s what keeps me going: somewhere right now, a coach is drilling their players on perfect technique in isolation. A teacher is having students practice procedures through repetition. A trainer is selling equipment designed for identical reps. A certification body is teaching future coaches to focus on body mechanics. A testing company is measuring skills in standardized conditions.

And somewhere else, a Cleveland Cavalier is adapting to a pool noodle in real time, building capabilities that traditional training says are impossible.

Somewhere, a surgical resident is learning 31% faster because their training includes variability.

Somewhere, a programmer is developing skills 34% more quickly because they’re solving constrained problems instead of following tutorials.

Somewhere, a student is retaining knowledge 43% better because they’re practicing with contextual interference instead of blocked repetition.

The future of learning already exists. It’s published. It’s validated. It’s proven at the highest levels. The only question is how long we’ll pretend it doesn’t.

I’m done pretending.

This isn’t just an investigation. It’s a line in the sand. On one side: forty years of research, overwhelmed by economic incentives and institutional inertia. On the other side: a global industry that profits from keeping people in the dark about how they actually learn.

I’m choosing the side of evidence. I’m choosing the side of human potential. I’m choosing the side that says we can learn faster, perform better, and achieve more than the training industry wants us to believe.

If you’re a researcher working on constraints-led approaches—I want to amplify your work.

If you’re a practitioner applying these principles and getting results the industry says are impossible—your story needs to be told.

If you’re an athlete or learner who’s discovered that CLA accelerates your development—you’re living proof that change is possible.

If you’re inside the training industry and see the economic forces preventing change—your insights could help us understand how to break through.

And if you’re a parent, teacher, coach, trainer, or anyone who helps others learn—you deserve to know that there’s a better way. One backed by decades of research. One that works.

The evidence exists. The research is published. The proof is in Cleveland’s 64 wins, in surgical residents learning 31% faster, in programmers developing skills 34% more quickly, in students retaining knowledge 43% better.

The question is no longer whether CLA works.

The question is: how many more years will we waste before we demand that the training industry acknowledge it?

How many more people need to learn slower than necessary?

How many more skills need to go unmastered?

How many more careers need to end earlier than they should?

How many more billions need to be spent on training that contradicts how the nervous system actually works?

This investigation continues. Every month brings new evidence. Every discovery deepens the indictment of an industry that profits from ignorance.

But investigations alone don’t change systems. Pressure does. Demand does. People refusing to accept suboptimal training does.

The Cavaliers won 64 games with a pool noodle and a theory that’s been validated for forty years.

Imagine what becomes possible when the rest of us stop accepting less.

This is CALIBRATE. This is where we draw the line between what the industry wants you to believe and what the science actually shows. The investigation continues. The evidence compounds. The truth demands a response.

Contact: elsnersam94@gmail.com

The research is clear. The resistance is economic. The choice is yours.

What side of history will you be on?

Sam, I really enjoyed this piece. You are making complete sense to me. I think that part of the issue here with adoption of the CLA is that fact that the majority of the information available is so technical/scientific that it’s hard for coaches to 1.) get their heads wrapped around it, 2.) once understood, put into practical application in their practices. With a small amount of adopters, it can be fairly daunting to coach in this way. It took me personally about a year of reading and listening to podcasts to really understand completely what is going on here. If you coach with others that are imbedded n the traditional model, it can be tough to get alignment. I appreciate the work you, and others (love Loren Anderson’s stuff as I’m a volleyball guy too) are doing to get this out there in layman’s terms and practical application. I know that’s it’s helped me a lot. Thanks!

THIS GOT ME FIRED UP